Project Description

Foraging in the Archives

for Arnoldia, Summer 2023

“We are continually overflowing toward those who preceded us, toward our origin, and toward those who seemingly come after us…. It is our task to imprint this temporary, perishable earth into ourselves so deeply, so painfully and passionately, that its essence can rise again ‘invisibly,’ inside us. We are the bees of the invisible. We wildly collect the honey of the visible, to store it in the great golden hive of the invisible.”

Rainer Maria Rilke

Say a lone honeybee, foraging for nectar, lands on a hidden patch of goldenrod several miles from the hive, on the other side of the mountain, in a little clearing next to a stream. In the afternoon sun, she drinks from some 50 to 200 flowers, until she is full. Then she flies back to the hive. Upon return, when her sisters see her, she vibrates her wings and abdomen at a particular amplitude, frequency, and angle—a certain shake, a certain quiver. She pivots in a figure-eight pattern in space, beating her wings as she cuts a straight line, then turns in a circle and holds her wings still.

With these complex gestures, the bee communicates the direction of the food source relative to the sun’s position in the sky; the duration of the dance indicates how far away the nectar lies. It is a dance performed for a singular occasion, constituting a kind of ephemeral archive, a record of the route to the nectar that fuels her dancing—a language, certainly. Having witnessed the dance, the other honeybees will find the patch of goldenrod blooming on the other side of the mountain and drink from it. The hive itself, its cells packed with honey, houses a physical record of every single wildflower that was visited by members of the hive in one place on Earth in a passing season, the sweet essence of each flower, inscribed into invisible-to-the-eye DNA traces. A drop of honey on your tongue is an archive of nectar slurped by the bristly tongues of forager bees, spit into the mouths of worker bees at the hive who held it under their tongues until it turned to honey, then stored it in cells within the hive.

The word archive can be traced to the Greek arkheion. The French philosopher Jacques Derrida tells us in Archive Fever (1995) that the arkheion was a house, a dwelling-place of the magistrates, where official documents were filed and stored. This leads us to the Greek oikos, the home or dwelling of a common person, the word that is at the root of ecology, and so ecology is the study of the home, every home an archive of ecological events and relationships.

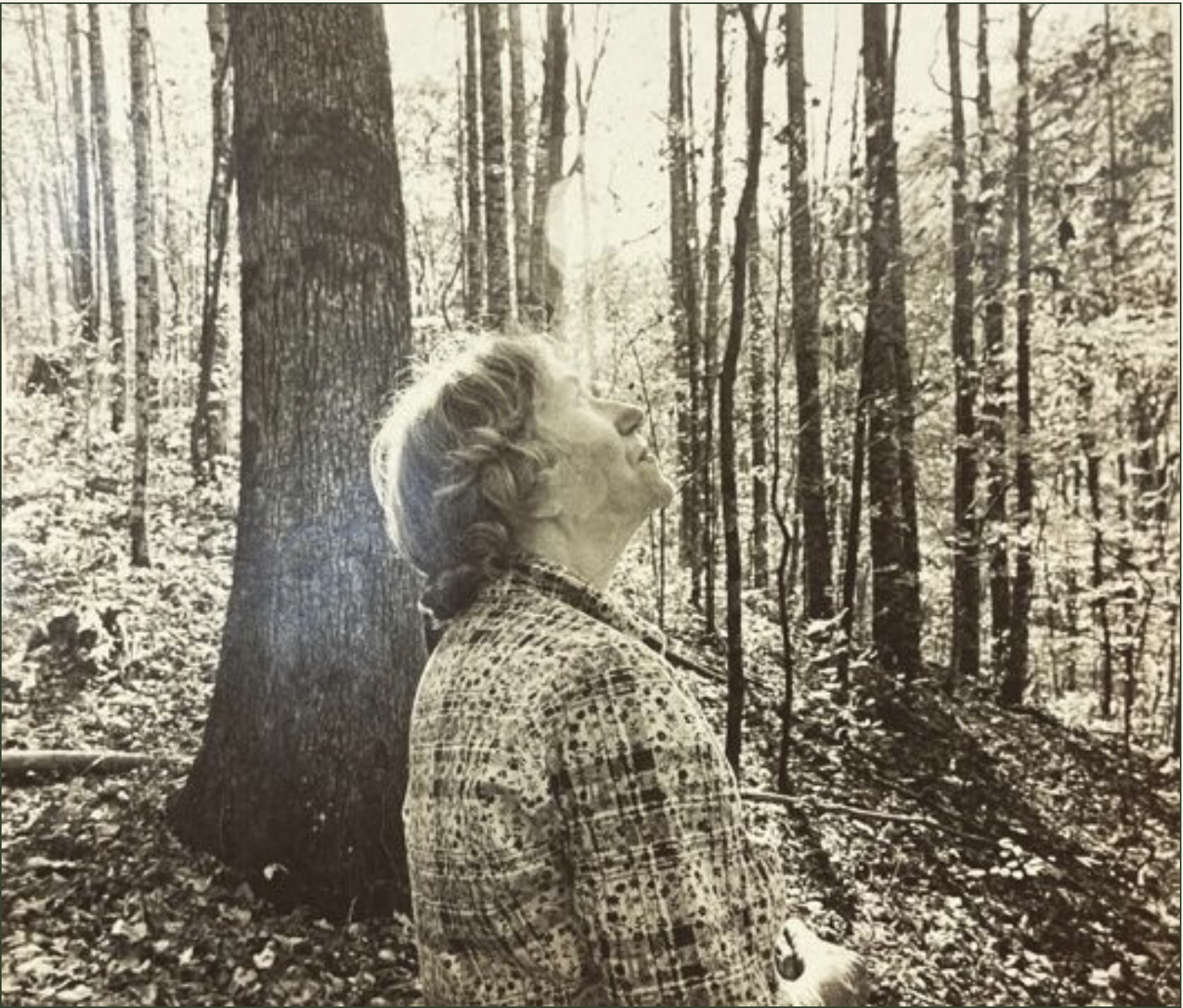

VISITING THE ARCHIVES at the University of Georgia, I landed on the 28-box collection of a botanist named Marie Mellinger. Born as Marie Barlow in 1914 at the edge of a forest in Wisconsin, she settled with her husband Mel Mellinger in Rabun County, Georgia in 1958, where she lived until her death in 2006.

A self-taught naturalist, she “built a scholarly reputation through exhaustive botanical surveys,” according to her obituary, and penned the Atlas of the Vascular Flora of Georgia. She became the first non-Atlanta president of the Georgia Botanical Society. The collection holds her scrapbooks of pressed flowering plants, an extensive and meticulous index of flowering plants with citations to published works that give further botanical information, clippings of stories about Mellinger from local and regional newspapers, and several sleeves of her 35 mm Kodachrome film slides of plants and landscapes.

As I dug through, I came across a hefty box containing Mellinger’s recipes for dishes prepared with wild edible plants native to or naturalized in the mountains of North Georgia. The box was stuffed full of hundreds of recipe cards, so packed with them that there was no empty space in which to flip the cards from one to the next, and I had to pull each one out to read it. I was immediately enamored with recipes for stews of chickweed, salads of cress and cattail shoots, wood-sorrel sauces, walnut-persimmon cakes, sautéed kudzu, and birch-leaf tea.

Recipe boxes have been kept throughout written history in the homes of common people—women, mostly, in the cabinets and on the counters of kitchens, the cards inside accruing splatters and stains over time from boiling pots and dripping spoons. Though they constitute significant archival efforts, these rich collections are rare in “the” archives, considered less significant in the annals of history filed at the houses of the magistrates.

Derrida reminds us that the archive is jussive—it decides not only what is remembered but what is memorable. The recipe boxes of mothers and grandmothers have been passed to daughters and granddaughters, home to home, living archives to which new recipes are added, old recipes pulled out of the box again and again. They were not deemed as memorable in official history as a host of men’s affairs were, though eating is the daily act that has fed and nourished everyone throughout history.

Records of foraged meals are even less archived, it seems, and this is what caught my eye about the box in the Marie Mellinger collection. They pointed not only to a meal prepared and eaten but to the unwritten, singular acts of gathering that the meals’ preparation required each time. These recipes gestured viscerally toward the mountains and fields beyond the kitchen in which Mellinger cooked, the oikos that gave her life sustenance.

Mellinger’s meals of wild edibles collected throughout the 1970s were set apart from the storebought culinary culture that rose to ascendance in the 1950s and still constitutes the industrial mainstream (which speaks also to ecological relationships), and even from the meals that one might prepare with vegetables harvested from a garden. They suggested not only field but forest, not only fertile valley but windswept ridge. A woman’s life not confined only to the grocery store or kitchen. A wider, wilder frame. To me, the box of recipes painted an intimate portrait of a life lived in a particular place on Earth, and its many passing seasons. A forager myself, for days I rifled through the box, as if to satisfy a hunger, to drink a nectar. Purslane pickles, burdock candy, dandelion coffee, smilax jelly, mulberry spritzer, sassafras tea, elder flower fritters, stewed chicken of the woods mushrooms.

Sitting in the quiet, stale, and light-filled reading room of the university’s archives, reading the recipes, I thought of roaming the woods. It was the middle of March, and sorrel was speckling the forest floor. Instead of sitting there, I might have been picking the heart-shaped leaves of violet and collecting them in a basket for a salad. It was the time to harvest chickweed, too, the leggy stems of which I would chop with my knife and blend with olive oil to make a green pesto. I would have liked to forage, to make a savory pie with henbit and cleavers. But I was held spellbound inside, foraging for sustenance of a different sort—a kind of sweet essence.

Mellinger’s archive of recipes made with foraged plants is not like the hive-archives of bees, not itself an edible honey. Yet, it is a record of wild plants that bloomed and grew, that were collected and eaten throughout a lifetime. The box of recipes seemed to be a record of motions as fleeting as the visitation of bee to flower.