Project Description

Write While Lying Down: On Finding Rest in Creative Labor

Holly Haworth Tries to Shelter the Muse From Economic Reality

for Lit Hub—

“Write while lying in bed,” I tell my creative-writing students. I am trying to get their attention, sure, and the suggestion carries a rebellious flair.

What I know that they don’t yet is that the weight of the work we have to do as artists, in a world in which time is money, can press so heavily upon us that, well, we need to lie down sometimes.

I’ve said that my students don’t know this yet, but I can see already engrained in them the years of writing in school to earn not money but the grade they want—the grade they now feel they need, so they can go on to a career that earns them enough money. I can see the worry knitted into their young brows. How deeply their creative process is already entrenched in concerns of an economy of one kind or another.

What I know that they don’t quite yet is that we have to find creative ways, even, of accessing our creative selves in a world in which grind culture gnaws always at our minds. Finding rest or refuge in our writing is a necessary skill for resilience, our shield against burnout, our sustenance for going the long haul. Telling my students is a way of reminding myself: the page can be a space of pleasure and play. Writing can be a restorative act that fortifies you for all the other work you will, no doubt, be compelled to do.

It’s a good utopian touchstone, anyway, this angle of repose, even if on most days, if we are being honest, the work won’t look or feel that way. That’s what I know, too.

In a culture obsessed with productivity and industry, many of us writers and artists have found ourselves pressured to argue the merit of what we do as bona fide work, especially those of us who try in some way to make a living at it. We know that it can be grueling, that it requires incredible energy, that it takes all of what we have to give. But in a culture that views writing and art-making as a kind of loafing around, we also have to do the work of earning respect, the validation that what we do is, actually, work.

Like a lot of writers, I suspect, I have often felt my work belittled and misunderstood by those whose work is more obviously industrious and profitable. I would guess that most of us have known the difficulty not only of getting words on the page but also justifying what we’re doing to others. And, of course, there is the grim reality of feeling that we must turn out words as commodity in order to survive.

And so we are accustomed to thinking and speaking in terms of daily word counts and page quotas, deadlines, and payments. Language people that we are, we have learned to use words from the business world both as a way to honor our own work as such and to prove to others that this writing stuff is real work. That is all very understandable.

The problem is that our language is powerful. We ourselves forget that while this is all very hard work for which we should, yes, be compensated, there is also something else at work in us, in the best of moments—something unspoken and beyond all that. There is something else that we are up to here. “Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing,” wrote the 13th-century Persian poet Rumi, “There is a field. I’ll meet you there. / When the soul lies down in that grass, / The world is too full to talk about.”

There is no language in this field where we lie down, and yet it sparks our verses.

The blank page is that field where we go to lie down, a field where our thoughts can stretch out, where we meet—in the best of moments—a world so full we have no words, and yet our words begin to bubble up as if from a wellspring, our thoughts begin to flower.

It takes so much work to get to the field these days. Grind culture and the attention economy grips our shoulder so tightly, dings in our ears, pushes notifications on us wherever we try to go.

That’s why we have to protect the work of writing as something that happens in a different kind of workspace, a private place. If not a place where we literally lie down—even if actually a desk, like the one where I sit now, or only a blank page and us, on a bus or the train—it is a place where we can hear the trickling stream of our memory, see the light of our lives shifting with the seasons and years, a place where go to reflect and dream, to see the world in its motion or stillness. It is a place where in some way we are able to slow time long enough to see a single moment, to have a single and complete thought. In Thoreau’s 1851 journal, I find this: “Only thought which is expressed by the mind in repose as it were lying on its back & contemplating the heavens—is adequately & fully expressed—”

Continue reading at LitHub >>>

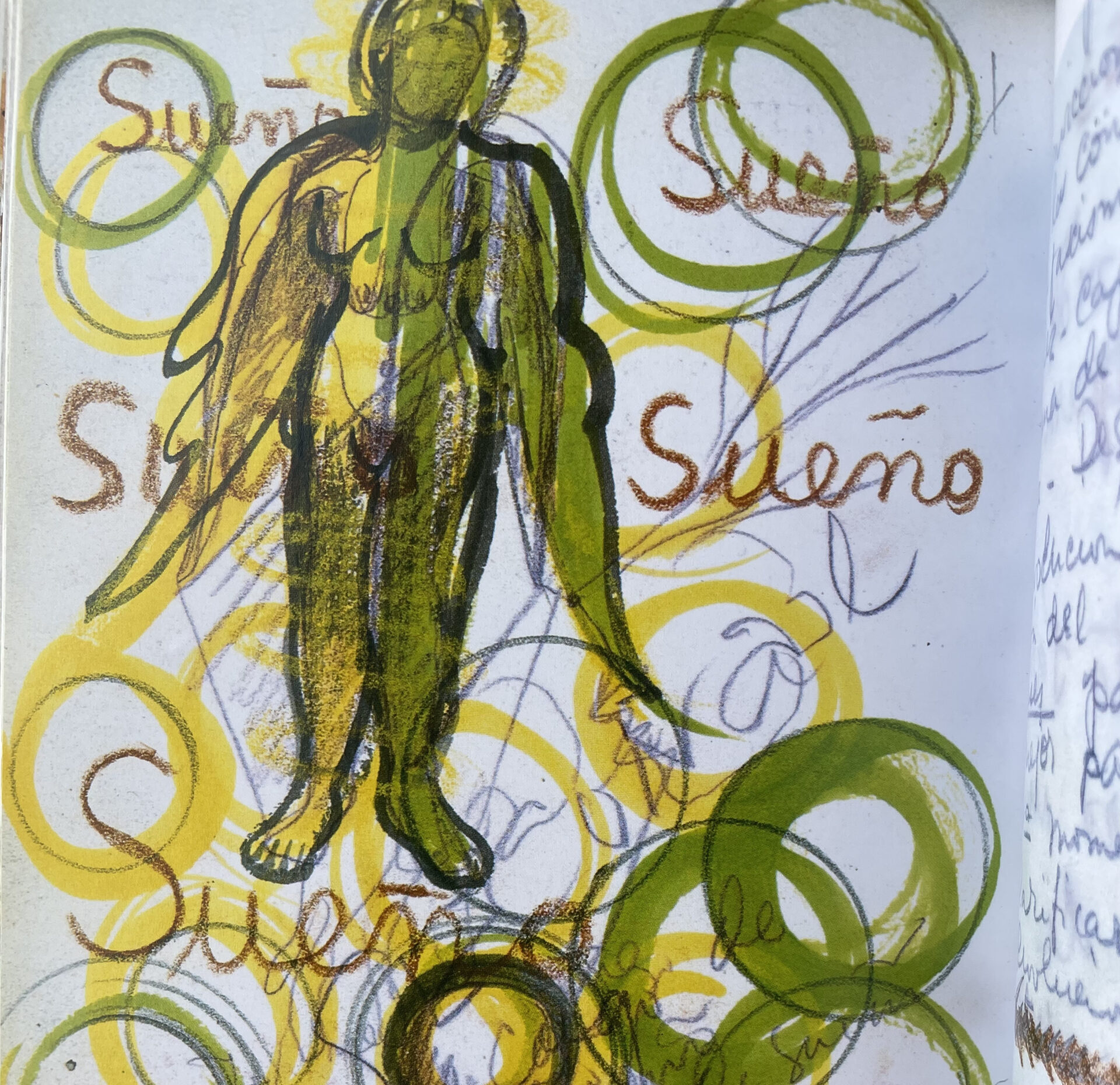

{The image is a page of The Diary of Frida Kahlo, Abram Books, 1995.}